Interview: The History Of The World As A Story Of Equality, Cooperation, And Resistance

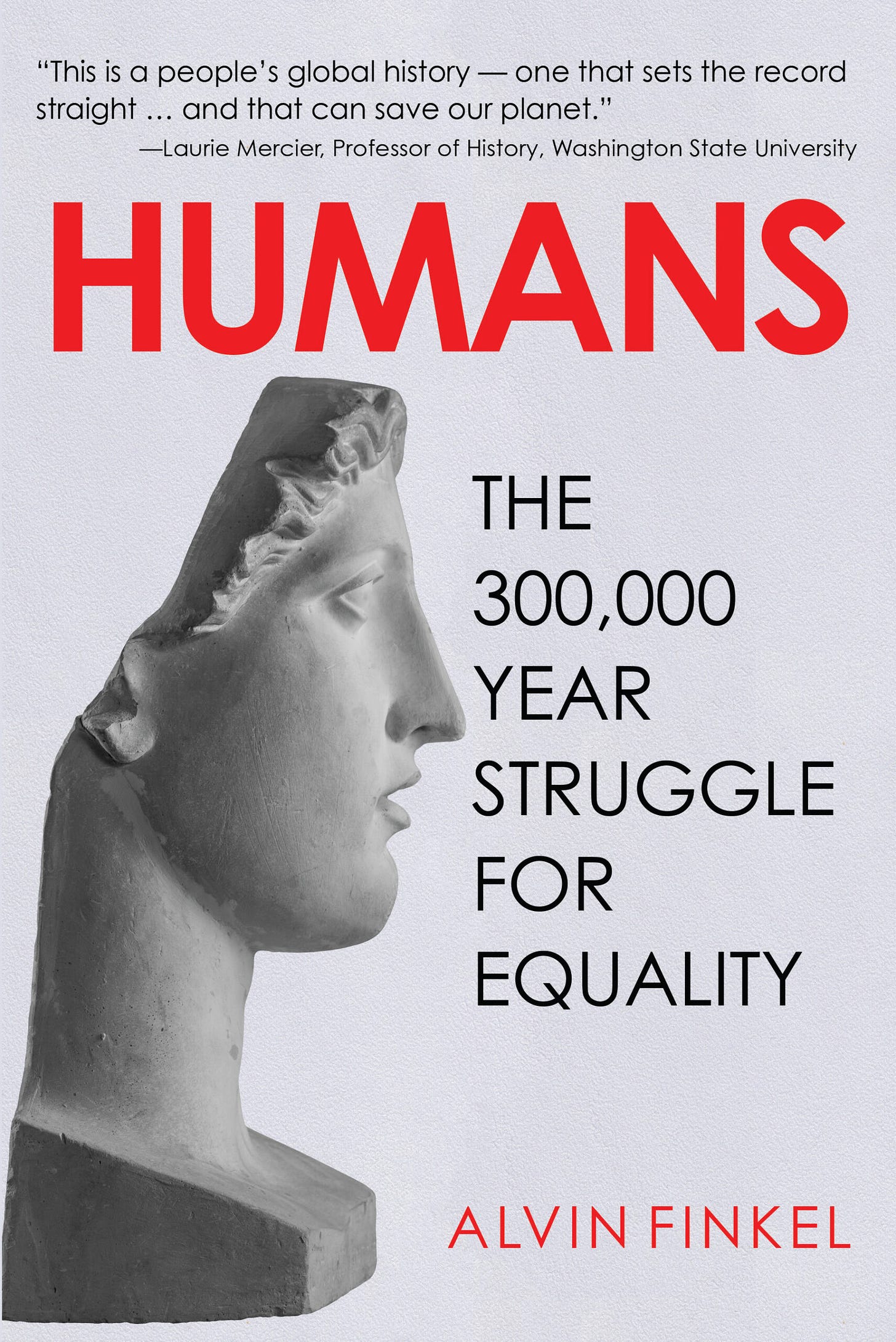

In this latest book, author Alvin Finkel looks to turn the story of humanity on its head.

Apologies for the late post this week. I’ve been sick — a natural reaction, I think, to the election. And speaking of elections, I’ll have more to write on here about that next week. But we’ve been so inundated with coverage that I wanted to mix it up a bit with a look at an important, fascinating topic. Onwards!

Alvin Finkel wants you to think about history in a different way. He argues history is too often written by the comfortable and the powerful, from the top down. He says a bottom-up look at human story tells a different tale, one of struggle, resistance, cooperation, and egalitarianism. In that history rests a hope for today, that we may grow a more equal and just political, economic, and social order.

I spoke with the emeritus professor and labour historian about his new book Human History: The 300,000 Year Struggle for Equality. I’m pleased to share that interview, edited for length and clarity, with you here.

David Moscrop

You argue that there's an “imprint of collectivist values that has dominated our history,” and that this represents 99% of our history. That’s an inversion of the focus of so much of the history we read, which is often the story of inequality and conflict. How did you come to focus on this 99% over the 1%?

Alvin Finkel

I've been an activist all of my life, but also somebody who reads a lot of history, and there seemed to be quite a disjunction between what I have learned from my own activism and from a lot of my readings and the emphasis in historical writing on a very small number of people. And it always seemed to raise the question of why are these guys getting away with it? Why was that?

David Moscrop

What is it about the historiography of the last several centuries that has come to focus on conflict and inequality over equality and cooperation?

Alvin Finkel

I think it has to do with who the historians are. They have largely been people from elite backgrounds, people who manage to get to universities, and there are people who don't represent a whole lot within the broader society. And so their thinking is very much like that of the people that were in control.

One thing I discovered in the 1990s was during a conference, where I wrote a paper on the way in which women were treated in the social policy literature. And I had thought that what I would find in terms of the writing before, say, the 1980s was a lot of pretty open sexism. In fact, what I found was that they didn't exist in the writing of the history of social policy; gender just wasn't there at all before a fair number of women started writing in the 1980s. And so I think you see that throughout historical writing, that until relatively recently, the people who were historians with people from very privileged backgrounds and the universities were not willing to let anybody into their hallow sanctums who had a different background or at a different point of view.

David Moscrop

So, we have been cooperative, peaceful, and egalitarian in the past. That way of living marks a major section of our history. But ours is also a history of conflict. What upsets those principles of organization?

Alvin Finkel

Through much of our history as a species, humans created collective societies, societies that were bottom up at some point for reasons that have partly to do with the special roles that were given to priests. Even in early societies that changed. And you had small groups who managed to obtain power. But what you find when you start looking in detail at these various societies of that kind is that from below, you had resistance throughout history to that kind of power. And some of the same spontaneity that existed in the early societies would reemerge in terms of people at the bottom organizing to either get back all the power they once had or at least to improve their position. So, I think that when you start focusing on what people from below were doing, you start seeing all kinds of things in history from a totally different point of view.

David Moscrop

Power is a central concept in your book, and you write about how the hoarding of wealth and the asymmetrical accumulation of power have produced these counter movements, these resistances from protest to revolution. What do other accounts of global human history get wrong or miss about relations of power? Do they even conceive of power in the first place?

Alvin Finkel

I think they do conceive of power, but what they tend to do is to see the power that small groups have as natural. And so they're not questioning how those people got that power. And then as various changes are made that appear to be changes at the top, they don't look at the impacts of what's going on below in causing that. An example would be the creation of so-called democracy in Athens where it is presented as the elite experimenting with giving power to some of the commoners. And those accounts ignore that over a third of Athenian society were slaves. And so they don't question, well, what role does that fact of slavery play in producing this so-called democracy? They don't look at the way in which property was distributed in that society.

I did find a number of articles that sort of obscure articles that looked at the kind of discussions that were going on when they decided to have this pretend democracy. And what stuck out was that the elite in Athens, like many elites, found that their power was very thinly based because they were facing constant revolts from the slaves, but also they had fairly frequent revolts from the Athenian-born commoners. The latter didn't like the fact that virtually all of the property had been appropriated by the small elite. Now they didn't make cause with the slaves who were captives, but the fear of the rulers at a certain point was that slaves seem to take advantage of revolts of commoners. And, similarly, commoners sometimes took advantage of the revolts of slaves to try and pressure the elites in the case of the slaves to topple the whole society. So the elite decided at a certain point that at some point we are not going to have sufficient military power to deal with a concerted revolt by slaves and commoners.

So we could get rid of slavery and have these captives from other places as a kind of bulwark against our own commoners. But then who's going to do all the work? So forget that. Instead, well, why don't we offer the commoners a few things that will cement the fact that they are above slaves in this society. We can have an assembly that can deal with many issues, but not the distribution of the property that's forbidden. And we will have an executive that isn't actually responsible to the assembly but is supposed to listen to them. And so that kind of phony participation that is from the top down but was called democracy, came out of a situation in which the elite understood that their power was in fact brittle.

And I think that we see that in a lot of other societies. I mean even the American South after all the so-called “white trash,” many of whom were people who had come from Europe and then indentured servants and had really no land and no privilege, but they weren't slaves. They were given the vote in the assemblies and made to feel that somehow they were real citizens. And of course the Black slaves were a whole class of people far below them. So, I think when you start looking at relations amongst groups in power terms, you interpret even what the elite are doing very differently, nevermind what the masses of society are doing.

David Moscrop

What are the moments in history, contingent moments, where the tendency towards an earlier history of cooperation and egalitarianism were upended? What was it something about the Agrarian Revolution, or about the development of capitalism, that turned history on its head?

Alvin Finkel

First of all, in terms of the Agrarian Revolution, it never happened. There's a movement from foraging to agriculture that happens over thousands of years everywhere. People don't just suddenly decide we want to be farmers. They introduce farming as a supplement to foraging, and then as it allows populations to grow, and then over time a felt need to be more sedentary grows. But in the early period of agriculture everywhere you find that in fact, the cooperative societies that existed under foraging continue because it's the same people. I mean that whole idea that the creation of agriculture suddenly causes cooperation and equality to disappear, it's just wrong. Organizational change comes later on as the character of agriculture becomes more technological and the priests are given power to build various dams and other technological things and use that power that they're given to actually create power over the people.

One good example of how agriculture doesn't really change very much is that during the scramble for Africa in about 1850, where all of the African societies are taken over by exploitative Europeans. All of the work that's been done on what those societies were like before the Europeans came suggests these were very egalitarian societies that when you look at the kinds of things that archeologists look at, like burial practices and whether there's walls these in communities and that these remained in fact egalitarian societies. So, agriculture itself hadn't changed anything important in the relations of humans.

David Moscrop

What about capitalism?

Alvin Finkel

Well, the common people played a big role in that too. They didn't want capitalism as such, but they wanted to destroy feudalism. What we were told in school was that feudalism was the result of a need felt by people throughout Europe after the death of the Roman Empire for the stability that the Roman Empire had provided. But when you look at the common people rather than the elites, you see that this is nonsense. I mean, the Roman Empire was an empire of total exploitation. The people who were conquered by Rome were either enslaved or they were made to pay enormous tribute to Rome for which they got nothing in return. So when the Roman Empire collapses in many areas, people's return to earlier kinds of society where they divide the land amongst themselves, they create democratic institutions sometimes that are not that formal, but sometimes quite formal. And so when these feudal lords come along offering protection, well, they're viewed pretty much like the mafia is viewed: We don't need you guys. You want us to agree to take an oath that we will give you half of what we grow and then give another eight or 9% to the church leaving us in dire poverty, fuck off. And they have militias and they try to fight that.

So feudalism is established everywhere really by force. And in many areas, in fact, the few, the lords, were never able to establish their role. And once feudalism is imposed in various places, there's constant revolt against it. I mean, much like there was against slavery, because in many ways it's a form of slavery. You don't really have any freedom of mobility. And in terms of what you grow, more than half of it is being stolen from you.And warfare continues. And at some point, I mean the people who are revolting want the return to the kind of societies that they had in many places between the death of the Roman Empire and the beginnings of feudalism.

In many areas what happens is that the landlord group decides, well, we're not able to prevent mobility of people. This idea that we own them and they have to stay on our land isn't going to work, but we're not going to give them the land either. What we're going to do is make them tenants. So, okay, while you're on my land, these are the rules. If you don't want to stay in my land, well, I can't stop you, but this is how we're going to organize society, that it'll still be a hierarchy, but you'll have a certain degree of mobility, that kind of thing. So the military power of the landlords continues, but the way in which they organize things changes and they create capitalism on the land, which then is imitated everywhere else.

David Moscrop

What about contemporary resistances to power? It’s difficult to be optimistic about the future right now, climate change alone, nuclear weapons, geopolitical dynamics, unfettered capitalism. What hope is there that we can rebalance our social and economic relations towards a cooperative, peaceful and egalitarian model?

Alvin Finkel

One of the things that we find through the history of capitalism is that although the bourgeoisie is oppressing people and the state is supporting the bourgeoisie, people do cooperate in their neighbourhood, in their workplaces, to try and rebalance things. So it's not like the cooperative idea disappears, it's just that it doesn't have much of an imprint at the top. But we did see in the period after the Second World War where people were so pissed off by what they'd experienced in the depression and the war that they were supporting a socialist transformation of society. So the state makes all kinds of concessions in order to ward that off.

That's still relatively recent. It is true that in that period after the war that the neighbourhood organization becomes somewhat weaker; the trade union movement weakens and becomes more focused on single work places rather than all of society. But I think the point is that we still have those kinds of organizations in society. We do have trade unions, we do have civil society groups. I guess the question is whether they can work together sufficiently to create a counter to bourgeois power. It's not assured, nothing is ever assured, but it's not like there's never any good news. As I point out in the book for example, that what's gone on in Bolivia in recent times is very encouraging. I mean, the changing Bolivia from this colonial society to a flurry national society of the Indigenous peoples who are still the majority there, and an emphasis on redistribution of wealth all actually in the most recent years in a parliamentary framework.

It's not like there's no examples in the world that we can build on, but we live in a very fractured world where the wealthy have this huge power to make us think that the way they've got things organized, it's the only way to organize it. So we need to focus on examples where they haven't quite succeeded and try to copy them. Even in the Western world, although Scandinavia is capitalist, its capitalism looks a lot different than the capitalism here.

There are other ways to organize ourselves, but we have to have our eyes and ears open to them. And we have to think about how people looked after each other in the past. I mean, we have a notion that we live in a so-called welfare state, though somehow that there seems to be all sorts of people who fall through every crack. But when we look at the period before, the welfare state, people in their various neighbourhoods or their ethnic organizations or in benevolent societies did try to look after each other If we know the history of people, there's lots to make us feel like things can change in the right direction, in the direction of collective power rather than the power of the Elon Musk and Donald Trump.

Fascinating and have ordered from Library as Alvin Finkel, note spelling. Thanks for bringing this book to our attention and another nail in the coffin of rule by neoliberalism, that is the elite. The distribution of wealth over the last 45 years has been so called trickle down. Really been a concentration of wealth and power in a few big corporations and our so called elite in North America especially

I’d just add that very structured societies are a feature of the irrigation-using cultures that are called the first civilizations. In return for a guaranteed food supply and large tradable surpluses, people needed to submit and belong to a hierarchy that could both organize large public works (digging canals, building dams, running pumps) and run a military that could protect these comparatively wealthy societies from envious neighbours and the many migrations that occurred as climates changed after the last Ice Age.