Six Books I've Loved (So Far) In 2025

Ahead of the end-of-year rush, here are some of the best books from my pile(s).

We’re still several weeks out from the close of 2025, but I think it’s safe to say 2025 was…a whole thing. I could do a round-up of the news, but I think right now most of us prefer to…run away from the news. I think that’s healthy. Because 2026? I’m assuming it’s going to be another whole thing. As these whole things unfold, I tend to take refuge in books. I’m willing to bet some of you do, too.

Sharing reads I enjoy is truly a pleasure for me. I hope reading about them is a pleasure for you. In the spirit of that hope, for the year-end, here are half a dozen books I’ve loved reading this year. Not all of them are new, but some are. As in the past, I’ve reviewed some of these books or interviewed their author. In those instances, as always, I’ve linked to the review or interview.

Between Two Rivers: Ancient Mesopotamia and the Birth of History by Moudhy Al-Rashid (non-fiction)

I reviewed this one for the Globe and Mail and the headline called it “a tour of ancient refuse and relics.” That’s a perfect encapsulation of the book, which is a brilliant history of Mesopotamia told through a tour of the world’s first “museum” (there’s more to say on the use of the word “museum” here, but I don’t want to spoil the surprise).

Al-Rashid’s history is all the things an accessible mass market history book should be: thorough, fascinating, quirky, and not a word too long. Object by object, she takes you on a trip back to the fertile crescent of humanity’s forebears. I swapped back and forth between reading the physical book and listening to the audiobook, which she reads. I recommend either or both. If you’re after an edifying, entertaining, and thoroughly human series of stories, add this book to your list.

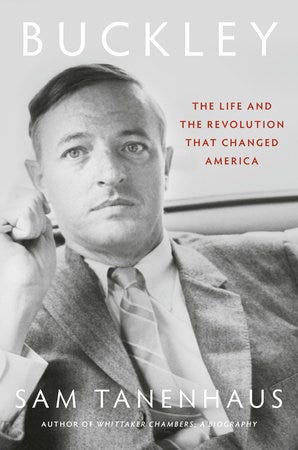

Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America by Sam Tanenhaus (non-fiction)

If you want to understand the contemporary United States, you need to understand the life, times, and project of the late conservative writer and movement leader William F. Buckley. With Buckley, Sam Tanenhaus has written a comprehensive account of Buckley’s life and work, a thorough and even telling of the man and his mission. It reads like a biography by Robert Caro, which is perhaps the highest compliment one can pay a biographer. The work of decades, Tanenhaus turned every page.

The most remarkable thing about the book — which…isn’t short, coming in at 1040 pages including notes — is Tanenhaus’s even keel assessments of Buckley and those in his orbit. He’s sympathetic to Buckley, and he understands his undertakings, but he never strays into defences or excuses for the National Review founder’s sins and shortcomings. The book is a commitment for a reader, but one worth making.

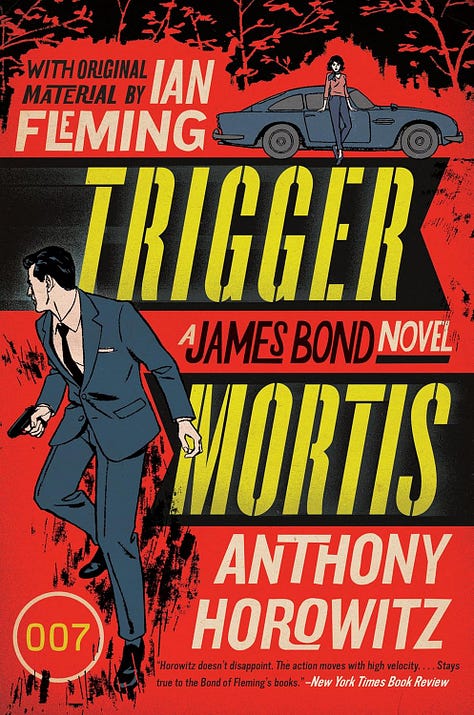

Trigger Mortis by Anthony Horowitz (fiction)

Last year, I closed the calendar by recommending Double or Nothing by Kim Sherwood, a new-ish series reviving both James Bond and introducing a cast of MI6 characters around whom the bulk of the stories revolve. It’s a great series. Before it came Anthony Horowitz’s Bond trilogy, including Trigger Mortis, set in the 1950s amidst the space race and Cold War intrigue. Though written in 2015, it’s thoroughly reminiscent of Ian Fleming’s Bond, though updated, for the most part, to meet contemporary sensibilities. It is…a welcome update, to say the least.

Also welcome is a brilliant pacing, Grand Prix racing, and rockets. But, honestly, Horowitz had me at the title — and the brilliant cover, which appears above but which I’ve also posted below because it’s so damned cool.

The Mind Mappers: Friendship, Betrayal, and the Obsessive Quest to Chart the Brain by Eric Andrew-Gee (non-fiction)

From the first pages of The Mind Mappers, I felt the tug of pathos. The story of neuroscientists and surgeons Wilder Penfield and William Cone, the book is in parts biography, history, and a study of complex personalities — and psychologies. It documents how a complicated relationship between two men shaped so much of brain science in the last century.

In my review of the book for the Globe, I wrote

This book is remarkable because it tells several stories in parallel, each of which intersects and enlivens the rest without any seeming superfluous, including histories in miniature of brain science, Canada, Quebec, Montreal, and McGill University throughout the early-to-mid 20th century. Mind Mappers is first and foremost, however, two stories. One is the mapping of the brain during an exciting and often gruesome era of discovery. The other is the relationship between Penfield and Cone, one heavy with pathos in its biographical details and the author’s own capacity for insight and compassion.

Months later, I still think about this book and the tragic story of Cone, above all, but also Penfield and the times in which both advanced medical science by leaps and bounds, extraordinary breakthroughs that came at extraordinary costs. This book will make many best of the year lists, and it deserves to.

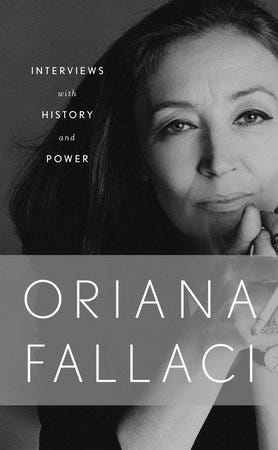

Interviews With History and Conversations with Power by Oriana Fallaci (non-fiction)

Oriana Fallaci is at best a figure of mixed repute. Her writing on Islam is quite reasonably criticized and condemned. Before that, however, her interviews with figures including Robert F. Kennedy, Henry Kissinger, Golda Meir, Willy Brandt, Yasir Arafat, and Muahamar Gaddafi made her a legend. These interviews and more are collected in Interviews With History and Conversations with Power, and they show an interviewer at the height of her powers, conducting courageous, well-informed conversations with powerful figures who shaped the world and its events.

The book doubles as a history of the last century and a guide to interviewing — a style at times subtle, at other times direct, and always honest. Typically poignant. A conversation, yes, but also a game of cat and mouse. Thorough without much, perhaps nothing, wasted. It’s such a cliché, and I hope you’ll forgive me for relying on it, but we could use such skill right now.

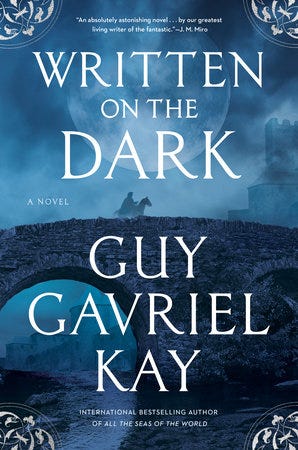

Written On the Dark by Guy Gavriel Kay (fiction)

You’ll be shocked, I’m sure, to learn that I reviewed Written On the Dark for the Globe and Mail. And I loved the novel. Guy Gavriel Kay is a legend, an iconic fantasy writer, and for good reason. He writes stories rich with historical allusions, literature that is at once compelling, entertaining, and edifying. His latest novel is the story of a tavern poet at the centre of a murder mystery, and high-power machinations set in a recognizable, if fictionalized, medieval France.

Reading Kay, I am often reminded of the Greeks, who knew tragedy and irony and comedy in ways we struggle to reach today, but to which we can scramble our way, if we try. The trying is worth it. If the effort is enjoyable, all the better. Written On the Dark is a blast to read, a pleasure. You can give it a surface read and enjoy a page-turner, or you choose to read more carefully, more deeply, and take more from it. Either way, it’s time well spent — especially if that time is passed in a cozy corner on a snowy afternoon or evening.

I loved Oriana Fallaci's book as well!!

Thanks for the tips! Enjoyed Guy Gavriel Kay on summer vacation.