Pierre Poilievre Is Spreading Bullshit. Does Anyone Care?

Can we fact-check our way to better politics? Not really. But sort of. Either way, it's worth trying.

Writing in the Toronto Star over the weekend, Raisa Patel fact-checked Pierre Poilievre’s claim that Justin Trudeau legalized ‘hard drugs’ in British Columbia. The piece is part of a series that “scrutinizes popular political slogans and talking points from the leaders of Canada’s major federal parties ahead of the next federal election.”

In the piece, Patel offers a readable, fact-heavy response to Poilievre’s bullshit claims around drug policy and their outcomes. She finds that the opposition leader was, let’s say, incorrect about his claims that Trudeau legalized illicit drugs throughout B.C. and that the province’s limited decriminalization drug policy has led to a massive jump in overdose deaths. Her work is a service, and you should read it and follow the Star’s series.

The good news is that journalists like Patel and outlets like the Star are doing fact-checking work. The balance of trustworthy information compared to mis- and disinformation (the former is sharing nonsense you think is true, the latter is sharing nonsense you know is false with the intent to deceive) is ever-shifting, and not in favour of the good stuff.

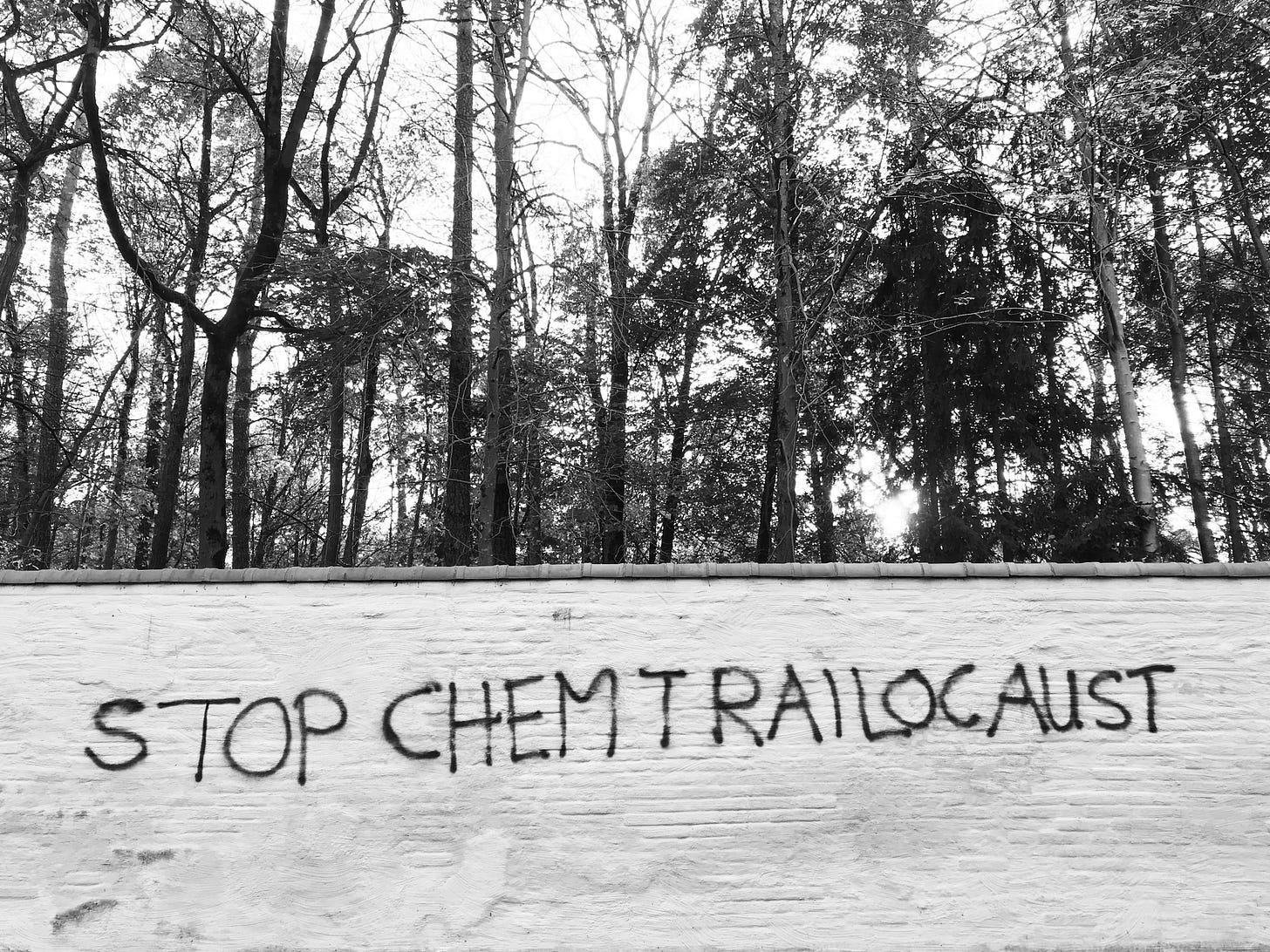

Politicians, media hacks, grifters, and both state and non-state actors often have a strategic interest in spreading bad information. Nonsense can help win elections, make money, or gain you an advantage in geopolitical relationships. Day-to-day consumers of that information are often ill-equipped to handle it: overburdened by life, lacking capacities to process information, or caught up in a social and/or psychological need to belong that leads them to believe and share mis- and disinformation.

The rise of social media and the outsourcing of the public sphere to private, for-profit corporations; the decline of legacy media; the rise of “media outlets” from god-knows where; and the meme-ification of news means finding trusted information is often tough. People left unsure where to go and easily sucked in by smooth talkers on YouTube or writers on forums who speak to their needs, anxieties, prejudices, and so forth.

While the internet has opened space for all kinds of alternative sites that offer valuable news and perspectives that have long been shut out by the mainstream, it’s also made it harder to know who or what to trust without reliable guides or starting points — and bad actors are ready and willing to weaponize that to their advantage.

Fact-checking is one way to address the surge of bad information, but it can only accomplish so much. Writing in the Conversation in January, Peter Cunliffe-Jones and Lucas Graves say

A series of studies published over recent years have shown that, while fact-checks will, of course, not alter an individual’s long-held worldview, they can and do have “significantly positive overall influence” on reader’s factual understanding and “reduce belief in misinformation, often durably so”.

They also point out a deeper problem with fact-checking and warning against bad information, namely that “those who see and believe misinformation are, often, not the same as those who see and believe the subsequent fact-checks. The two audiences often do not cross over.”

It’s wrong to think the world is exclusively populated with bad actors and dolts such that all anyone believes is untrue and irredeemably so. But strategic actors and their audiences are often united in their interest of sharing and believing in bogus ‘facts’ and worldviews that serve their political, economic, social, and psychological ends, and that’s hard to fight.

These powerful and often-related goals and incentives mean that for many fact checking — or flooding the market with better information in the first place — while effective in certain cases, will only go so far. If some people don’t truly care about facts and accuracy in the first place, it doesn’t really matter that you’re trying to provide better information for them. They don’t want it. Better information isn’t their goal.

There are still good reasons to fact-check and to provide reliable, accurate information and rigorous, informed commentary. You’ll never reach everyone, but that’s true of just about every public good (or everything, come to think of it). You’ll still reach some people, and you’ll shift the balance of good information versus bad information, create a disincentive to produce mis- and disinformation, and thus create at least a slightly healthier public sphere.

The true believers of bullshit won’t disappear in the face of good information. People who are truly motivated to believe this stuff will find someone to provide them the lies and half-truths they crave. They’ll turn out to vote, and they’ll take to the streets. But the effects of their commitment to nonsense can be somewhat contained.

For people looking to check their own consumption and habits, I recommend a few common approaches that can help.

Finding a few individuals or organizations you trust can go a long way to ensuring you’re getting good information. You can watch what they say and share and go from there. But that assumes you have a good sense of who or what’s reputable in the first place.

Even mainstream outlets platform charlatans and sometimes uncritically reproduce political statements that are utterly false. But at some point you have to rely on your judgment; it’s just good to be willing to second-guess yourself before committing to a belief.

Mainstream outlets are nonetheless a fine place to start this process. So are major NGOs and international bodies. Ditto universities and the experts they employ. Again, not all these sources say ought to be taken as the gospel truth, but you need a footing. And, as a rule, be sure to be wary of social media sharers, especially if they’re anonymous or just seem a bit janky.

The next step is to push beyond the boundaries of the familiar and think hard about who you’re listening to and why. Just because a site is independent or an expert isn’t platformed by the mainstream, it doesn’t follow they aren’t any good. Some of the best information I get is from sites, journalists, and academics beyond the boundaries of the big players. Again, develop your critical thinking skills and judgment as you go, and be open to these sources.

Once you do come across information you think you can trust, try to read all of it. Don’t laugh. You may be surprised at the number of people who share things they haven’t read or get most of their information from a headline or quote tweet of an article.

Not everyone can (or wants to) do their own research for everything — certainly not primary research and often not even secondary. But it’s easy enough to cross-reference and fact-check certain things. Taking a minute to search, double-check, and consider alternative arguments can make a difference, slowing down your thinking a bit and kicking you off cognitive auto-pilot.

Trusting your gut goes a long way, too. If something looks off, or someone seems unreliable to you (especially a politician), something in your head is telling you to proceed with caution. Listen to that voice. Memes are funny. I love them. They’re also a key vector for bullshit. If you see some random stat on a meme, maybe double check it before believing or spreading it.

I could say a lot more, but by 1,200 words most people have gone off to play Candy Crush (do people still play that? I’m deep into Slay the Spire), so I’ll leave it there. But I wanted to remind folks that fact-checking can be good even if it’s imperfect, we shouldn’t be too quick or willing to trust, and we ought to remain vigilant about what we consume and share.

I couldn’t like this more, thank you!

I was fortunate to learn research methods in university, and I taught critical thinking and media literacy to kids from JK to 6th grade. Learning to question everything (Is this true? How do I know?), finding primary sources, asking questions about who might stand to benefit from sharing specific information that’s not true, and who might be harmed by it…are all good places to start. The more we learn to question the firehose of mis/disinformation coming at us, the healthier our society will be. These skills are foundational to being able to sort through the increasingly murky information landscape we’re dealing with today.

My suggestion as we talk to people in our families and communities about disinformation: start with some of these questions. Set the table with the stuff we agree on: we all want the best for our country, and our families. If the conversation veers off into misinformation territory, then ask some questions about where the beliefs or information came from, and see if we can find solid sources together. Sometimes we can gentle people into questioning their beliefs, and sometimes we can’t, but it’s worth a try.

It is definitely worth trying. The one thing we cannot do is throw our hands in the air and give up. Thank you for this.